The BCA’s Press Conference Raises More Questions Than It Answers

Superintendent Drew Evans insists the breath test errors were recent and limited — but records show the BCA knew about them two years ago.

Yesterday, on October 13, 2025, at 5 PM, Superintendent Drew Evans of the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) held a press conference to address what he described as “human errors” in the state’s breath alcohol testing program.

The BCA’s message was clear: the issue was recent, limited in scope, and already under control.

Evans emphasized that only about 275 tests might be affected, that the instruments themselves remain reliable, and that the Bureau had acted swiftly once notified on September 12.

But the record tells a different story.

Documents, internal communications, and even a 2023 law enforcement report show that the BCA knew about this exact problem more than two years ago, and initially defended the accuracy of tests that were later proven unreliable.

Even more troubling, the BCA didn’t uncover this issue through its own internal quality control processes.

It was defense attorneys and their independent forensic experts (Chuck Ramsay and me) who identified the dry gas cylinder errors, not an internal audit, not a BCA inspection, and not any proactive review by the agency itself.

The press conference was meant to restore confidence. Instead, it exposed just how incomplete the official narrative remains.

The BCA Knew Long Before September 2025

At the press conference, Evans said the Bureau first learned of the DMT dry gas problem on September 12, 2025.

But that claim doesn’t line up with the evidence.

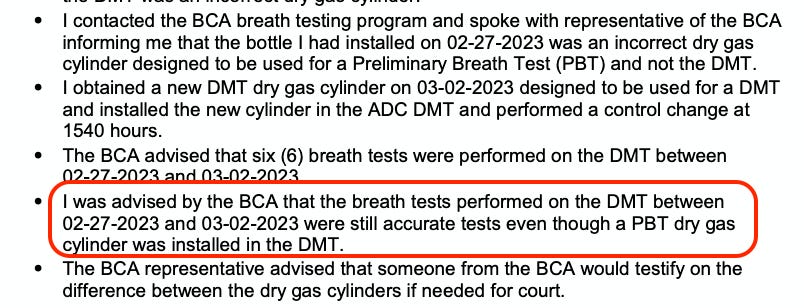

The Olmsted County Sheriff’s Office report from early 2023 documents that the BCA already knew about this issue more than two years ago.

In that report, an officer wrote that the BCA “advised that the breath tests performed on the DMT between 02-27-2023 and 03-02-2023 were still accurate tests even though a PBT dry gas cylinder was installed in the DMT.”

Rather than investigate or issue a statewide alert, the BCA stood behind those results. Only after Chuck Ramsay and I published our June 2025 peer-reviewed article exposing the problem did the Bureau reverse course.

“Case by Case” vs. Categorical Rejection

Evans said each test would be reviewed “on a case-by-case basis.” But that statement is also inconsistent with the BCA’s own communications.

In Aitkin County, BCA scientists wrote that they “cannot support this type of testing” and “cannot testify in court to the accuracy of these results.”

That’s not a nuanced, individual review; it’s a categorical rejection of an entire set of tests performed under invalid conditions.

The BCA Has Started to Act — But Only After Public Pressure

In fairness, some of the steps Superintendent Evans announced reflect recommendations I outlined in my earlier post, “The Five Whys: A Root Cause Analysis of Minnesota’s Breath Testing Failures”.

The BCA has now decided that:

Only trained BCA scientists and technicians will perform dry gas cylinder changes.

Local law enforcement operators will no longer have access to the cylinder compartment.

A lockout procedure will be implemented to prevent unauthorized changes.

These are important first steps, and they directly mirror some of the solutions I proposed.

But what’s still missing are the two most important reforms: independent external review and public transparency.

Without those, the same problems that went unnoticed for years can simply resurface in another form.

What Was Missing

Several key issues went unmentioned in Evans’s press conference, and their absence speaks volumes.

No independent oversight.

The BCA continues to investigate itself. There was no announcement of an external audit, third-party review, or invitation for independent experts to verify the quality assurance data.No commitment to public transparency.

Evans did not address whether the BCA would make quality-assurance data publicly accessible, despite national recommendations for forensic transparency.No acknowledgment of past cases.

The BCA’s focus remains on the currently identified 275 tests. But the same equipment has been in use for more than a decade. If these issues date back to 2023 or earlier, what about the thousands of past DWI convictions that may have relied on similarly flawed testing?

The Real Lesson

Evans’ press conference was meant to project confidence. Instead, it underscored a deeper truth: Minnesota’s breath-testing program still lacks independent oversight, public transparency, and full accountability.

Real progress will come when that control is balanced with independent verification, when outside experts can access and evaluate the data themselves. Only then can the BCA fully demonstrate the integrity and transparency it says it values.

The BCA defines Integrity as “the cornerstone of public trust” and a commitment to “always do the right thing.”

Living up to that value now means more than reassuring words at a press conference.

Automated Transcript of BCA Press Conference (not checked for errors)

[00:00:00] Drew Evans: Good afternoon, everyone, and thank you for, uh, joining us here today. My name is Drew Evans. I’m the superintendent here at the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. There’s been a lot of interest in some recent, um, guidance that we’ve put out to Minnesota law enforcement on inspection of our DMTs or data master, uh, transportable machines is what they’re referred to and what that means in the impact of Minnesota law enforcement. Before I do that though, I’d like to give a little bit of background on the instrumentation to level set exactly what these, uh, instruments do and what they don’t do for us. In Minnesota, there’s currently 220 instruments that are deployed across the state of Minnesota and approximately 4,500 users that utilize, uh, these instrumentation to conduct breath alcohol tests on individuals that are suspected of driving while intoxicated.

[00:00:53] In that process, they all go undergo extensive training on how to use the instrumentation for our law enforcement partners. And then there’s some pieces that go with this that have brought you here today. What we’ve uncovered in the, once we were first notified about this is that there’s been a number of human errors that we’ve identified with these instrumentations in particular when changing out a dry gas cylinder that is used for a control test.

[00:01:17] And in that process, it’s important that that’s done correctly. Uh, and with, uh, and some errors have been discovered, uh, in that process. Minnesota users every single year conduct approximately 19 to 20,000 tests, and we’re at 15,000 tests across Minnesota. So far in this process that we’ve identified where there’s been human errors in terms of changing out these gas cylinders that we have approximately, um.

[00:01:41] 275 tests that may be impacted. That’s what’s important to know in this, that every one of those cases need to be individually examined by, uh, prosecutors of the Attorney General’s office that are working through that to determine whether or not that test was impacted. Here’s what we’re doing in this process last Friday.

[00:01:59] We notified all Minnesota, uh, users of this instrumentation that they need to check the instrument. And it’s important for everybody to know that these instruments at those locations across Minnesota are at locations to be used by any of the users that may be using it in there. And what that means is a particular agency, or in this case when we’ve identified counties or locations where these machines might be the heirs that occurred, may or may not have been done by those agencies.

[00:02:28] Part of the agreement with these is to ensure that everybody has access to the machines, is that all law enforcement in the area has the ability to use the machines. So it’s an important fact that when this airs with changing out the cylinder may have been done by another entity. When we’re working through that process.

[00:02:44] The inspection that we asked is we did not take the fleet completely offline. What we did is we asked for the fleet not to be used any of the instrumentation until a simple five minute check can be done. What that involves is removing the cylinder and ensuring the information that is on the cylinder, which I’ll show you in a moment, is accurate in the machine, and that a control change test is performed to ensure that it matches the information after they reinsert it in their process.

[00:03:10] This has not impacted Minnesota law enforcement’s ability to conduct DWI enforcement across Minnesota. Many of the machines were, uh, examined in that period, and they can go right back online because they’re accurate in the testing process and they can use the machines again, or law enforcement if a machine is not available, can engage in toxicology testing, which we also have that laboratory here at the BCA as well to test alcohol content in, uh, blood and urine and other substances, which we do on a regular basis. I wanna be clear that these instruments, we have complete faith in the instrumentation and the accuracy of the test results.

[00:03:43] These areas that occurred in this process are a result of this change, not several factors that might have been in that process. So what we’re doing going forward after this inspection is that in order to, um, ensure. That, uh, we have less people working on these and changing ‘em. Again, I noted there are 4,500 users across Minnesota.

[00:04:02] That’s a large number of people that have to revert back to their training. That may not change these on a regular basis, where we have a calibration team that manages and inspects and maintains this fleet here at the BCA. They will take over going forward the changing those gas cylinders. It’s not that law enforcement doesn’t do this well.

[00:04:18] Tens of thousands of cases every single year, and they change out these cylinders. It’s that when we learn of some errors, we think through critically here at the BCA, how we can eliminate those. And by bringing this change process into a fewer number of people, we’re able to eliminate some of those errors along the way.

[00:04:34] We’re working on that as quickly as possible, uh, across the state of Minnesota, and we’ll also make sure that those cylinders are no longer accessible by anybody other than the scientists that work here at the BCA and technicians that are working on these instruments every single day. I want to thank our Minnesota law enforcement partners for paying prompt attention to the requests came on a Friday, coming into a busy weekend, but once we learned of additional locations where there were a variety of errors from either the wrong cylinder.

[00:05:02] Uh, being installed that was not provided by us. We provide the cylinders or data entry error in that process that we felt it was incumbent, that we get the information out as quickly as possible so that our law enforcement partners can inspect ‘em. ‘cause the last thing they want is to have a, a breath test that could potentially be impacted as they’re working diligently every single day to remove impaired drivers from Minnesota roads across Minnesota.

[00:05:25] I’m gonna step over to the other table just quickly to show you what I’m referencing and then take some questions. So this is a DMT machine that are used across all of Minnesota. This is our current fleet that we’re using, and the cylinders in question are these cylinders here, they have information printed on the outside of the cylinder.

[00:05:44] These are then input into the back of the machine, inserted into this machine, and then the information is put. If any of this information, I shouldn’t say any if some of this information is entered incorrectly. It could create a challenge for this and the reliability of the particular test. However, there’s other pieces of this that could be entered incorrectly and we’ll show that error in the process, but it may not impact the actual reliability of the test.

[00:06:11] That’s why we say it’s important that we work through each case individually with prosecutors and the Attorney General’s office and the implied consent side to determine whether or not the test is actually impacted going forward. This dry gas is provided by the BCA. And we provide these for all of the instrumentation across the state of Minnesota in that process.

[00:06:33] With that, I would be, uh, happy to, to an

[00:06:43] Audience: time period there.

[00:06:47] Drew Evans: Well, part of what we asked for in this process is to ask to this inspection. So to date, we have not received any additional, uh, contact from agencies saying there’s different challenges with that. However, of the five counties that we’re aware of that have had some challenges, they’re all slightly nuanced.

[00:07:05] Issues. They’re all slightly different, so we need to look at them one-on-one as we go through to determine whether or not it impacts the actual case. We are first notified of the first issue on September 12th, but we’ll be working as part of this inspection process to determine if any others have challenges with them.

[00:07:22] Also, it should mention that all machines across Minnesota are calibrated in our laboratory once a year. And so we see the machines as they come in, and the part of the inspection process is examining the cylinder that’s in there when we receive that. And we had not seen the same issue that we’ve seen in this particular case going back.

[00:07:40] So the timeframe we’re looking at right now is looking at the current fleet that’s deployed within that period of time, and then we’ll address any additional issues as they come up, uh, through the process as people, you know, mount any challenges or questions or inquire about the various machines and the, the testing across Minnesota.

[00:07:59] Audience: Aware of this last month, what was the reason for the.

[00:08:11] Drew Evans: Yeah. So the question was, uh, for others is that the, if we were aware of this in September 12th, why, uh, was the review recently ordered as part of this process when that first instrumentation came in or that the notification as part of that process? We had no reason to believe it was a more widespread problem with the instrumentation.

[00:08:31] As we’ve been notified of some of the others that I said, they’re all unique instances that appeared to be. Uh, individualized and as we learned over the last, uh, as we’ve been working through the review on our own, we determined that this potentially could be more widespread given that there was similarity between some of the issues.

[00:08:48] And that’s why we issued the request, uh, to inspect all these machines before using them. Further to make sure that that data entry error did not occur in any of the others. It’s important to know that this instrumentation, you know, is, um, uh, reliable and it’s, it has, uh, the testing itself. Uh, it is in terms of how the instrumentation works, uh, is a reliable machine and it works well in that process and those data entry error may or may not actually impact the validity of the results in that process.

[00:09:15] So it takes us some time, as I said, there’s, you know, 20,000 tests a year to. Go through some of the data that we have available to determine whether or not this was something that we needed to do inspection, or if it was one or two off issues that we identified by self-reporting. I’ll note one of the counties, even after this happened, they were doing their own change process that identified for us and they followed their training.

[00:09:36] Exactly. They changed it out. They notified us that there was a problem with this, and we addressed that in there. That was the, the second two that we were working on in the. The third actually in the process that we’re notified of in that process. So, uh, certainly, uh, the checks and the training and the quality controls we have in place worked in some instances and we wanted make sure that others where it may not have that we go forward with that process forward.

[00:10:03] Audience: Is there any sense of how this happened?

[00:10:08] Drew Evans: Well, again, with, you know, 4,500 users across Minnesota that are using this instrumentation that have to look through that process, human error, whenever there’s humans involved in something, there’s always potential for human error. That’s part of why we’re looking at this process now and, and narrowing the number of people that will handle this, that do this every single day, and that their full-time job is the maintenance, inspection and repair of these machines, so that, that’s reviewing it.

[00:10:33] Again, with that many users and human error, once this issue’s been identified for us, uh, it’s not that law enforcement doesn’t do it correctly. There’s thousands and thousands of tests over many years where they’ve done a great job with this. It’s a matter of looking at if we identify an issue, what other ways can we work on to support our law enforcement partners across Minnesota to make sure that their, uh, testing is not impacted by a simple human error like this.

[00:10:59] So right now we know of, um, five different situations, but we’re continuing to look at that and certainly that may be additional as we ask them to inspect. We just asked them on Friday to inspect. We didn’t give them a timeframe to do that. We asked ‘em to inspect, not use the instrument until they have the ability to do that and contact us with any, uh, challenge problems that they see.

[00:11:18] And we have not heard from anybody yet, but it could, it could, we could hear from others and that’s fine.

[00:11:23] Audience: How many? 220.

[00:11:27] That number is at 275.

[00:11:30] Drew Evans: Yeah, it certainly could grow. Again, we haven’t been contacted today and we issued this and you know, we’ve certainly heard from some law enforcement, we’ve heard, we fielded questions all weekend long from law enforcement asking about this process.

[00:11:42] So we know they had ah, jumped on this and were very prompt, uh, to, to looking at these devices. So we assume that the majority of them that were quick to look at this did not find any problems with the device. But we’ll continue to look at that. And then also the data from the devices in the past.

[00:12:00] Well, great question. So I mean, the, the, it’s a three day training now, 24 hours of training that go into the proper use, uh, in administration of breath alcohol tests in Minnesota. But part of that training is going to be, don’t, uh, remove the gas cylinder. So we’re going to do that in that process and that’ll eliminate most of this particular issue because we will be the ones putting all that data in and doing that day in, day out.

[00:12:23] Uh, so that we think is an easy way for us to be able to address this issue on that. But the training also as they go through. It’s very detailed in terms of how they go through each step. And part of our notification this week on this particular was to send out, uh, a detailed step-by-step instructions for how they would go through and, and change, do the inspection on this and, and remind them of the training in the manual about the proper changing out of that.

[00:12:48] But we are telling them do not change them at all, and we’ll be locking down the instrumentation going forward.

[00:12:59] Audience: Yeah, but.

[00:13:08] Drew Evans: Yeah, so certainly we’re under a review process right now, and that’ll be part of the process, which is to work together with the attorneys. Obviously, we can’t comment on, you know, pending litigation, and there certainly could be with these. So we’ll be doing that review working together with county attorneys and the Attorney General’s office, uh, in part of this process, looking to determine if any cases going further back would be impacted.

[00:13:32] When they’re writing numbers down correctly or, yeah, so on a canister like this, there’s a lot number, just as an explanation, there’s the alcohol concentration that’s listed here that this is originally.

[00:13:49] And then an expiration date that’s on here. Some of that information could, is then all the information is then entered into the machine so that it knows which dry gas cylinder is in the particular machine. And then in particular, that alcohol concentration. If that is wrong, it runs a control test. But these are, they have such low tolerances that it could potentially.

[00:14:11] Um, not air out in that change process if it was just transposed a bit, but it’s important for us to have all that information entered in accurately. Again, though, if some of this information, like this lot number was not necessarily entered in 100% correct, that may not impact the validity of the particular test.

[00:14:28] It has to do with some of the other data. That’s why we have to work through it on a case-by-case basis with each of the tests to determine how the attorneys want to handle the particular case.

[00:14:45] I’m not, uh, I’m aware of a couple of issues in particular with, uh, the canister not being used, uh, correctly provided by us, uh, in the past that we address with the agency, but the canister may or may not. Impact the actual validity of the results that canister doesn’t have to be provided by. It has to be provided by us, by our own guidance, but it doesn’t mean that the actual cylinder would be incorrect if it was by another third party supplier or a different canister.

[00:15:13] We do that as a quality control measure here at the BCA, so we know which dry gas cylinders are going in our instrumentation as part of our accreditation process, which is our quality standards for our laboratory here.

[00:15:27] Uh, I believe this Fleet, 2012, I believe is one first one into, uh, that. I’m seeing 20 11, 20 11, 20 12, uh, in that process. But this particular fleet’s been in, we’ve been looking at, uh, replacement fleet. It’s a decade or or more old at this point in time. So certainly that’s been on our radar for a while now.

[00:15:47] We’re working through that. And part of that process is always looking at how do we improve the fleet that’s in there, you know, with this, uh, process, obviously this is an efficient way to measure blood alcohol out as opposed to going through, uh, toxicology, which is a very accurate measurement as well.

[00:16:03] But it requires getting a search warrant, uh, to gather that so it takes a law enforcement more time. So that’s why the utility of our fleet remains in Minnesota and why we’ve looked to have these instruments across the state.

[00:16:18] Yeah, the great question. So just to be clear, question is about how any idea how long it’ll last, it lasts until they inspect the machine and ensure it’s the right canister. That’s it. So they, the, the instructions were to go back on line, it’s a five minute inspection, make sure it’s the right canister, all the information matches.

[00:16:35] And then that instrument, that particular instrument can be used again. We did not suspend the fleet hole until it was a green light by the BCA. It was make sure that you inspect this to make sure the information is accurate so it doesn’t impact any tests moving forward. And then they can use the instrument again.

[00:16:50] We have full faith, uh, in the instrumentation and the validity of the results if everything is entered correctly. One more question. So is it possible that. That there.

[00:17:08] Well, in theory, if that information, it wasn’t caught along the way, certainly there’s cases if that same error and nobody caught it, uh, certainly could be in that. Never could say that there wasn’t in that process. But what is important to know is this is a bit nuanced and technical. It doesn’t necessarily mean even if there were errors, that the test results themselves were not reliable.

[00:17:28] And so they would need to be identified and work through that process because again, while this is a, a very technical piece of this equipment, the reliability of the results really do need to be examined on a case by case basis. When we identify the a hundred plus, uh, 276 cases that we’ve identified for you, that could be impacted, that’s out of an extreme abundance of caution that we’re looking through, that we’re saying we need to get in and have.

[00:17:51] Other people take a look at this and work through these cases individually to determine whether or not they’ve been impacted. And that’s what we do in our, our laboratory. We hold ourselves to the highest standards of quality in the process, and that’s why we’ve taken the steps that we have to make sure that we are being as best a partner to our Minnesota law enforcement as we can, so that Minnesotans can trust the results and that we can ensure that impaired drivers are held accountable for their conduct.

[00:18:16] Thank you.