Beyond the ‘Typo’: The Real Story Behind Minnesota’s Breath Test Failures

The BCA calls it a data-entry mistake. In reality, it’s a preventable systems failure experts warned about months ago.

On October 10, 2025, the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (BCA) ordered a statewide inspection and temporary suspension of DataMaster DMT breath testing. Their public statement called the issue a series of “data entry errors;” trained operators were typing the wrong dry gas cylinder lot numbers into the DMT breath alcohol analyzer.

But that explanation isn’t the whole story.

Across Minnesota, officers have been found not just mistyping numbers but using the wrong type of dry gas entirely, substituting cylinders designed for portable PBT (preliminary breath test) devices into infrared DMT instruments.

These aren’t just typographical errors; they’re systemic process failures that undermine the reliability of every test result tied to those instruments.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because Chuck Ramsay and I warned about this exact issue months ago in our peer-reviewed article, Errors in toxicology testing and the need for full discovery, published in Forensic Science International: Synergy in June 2025:

“In 2023, a Minnesota breath alcohol test operator ran a series of evidential breath alcohol tests on the DataMaster DMT, an infrared analyzer, using a type of dry gas reference material intended for use in fuel cell breath alcohol analyzers... The use of inappropriate reference material raised questions about the veracity of the test results.”

Since then, the same error has surfaced across the state. The error has been found in Aitkin, Hennepin, Olmsted, Winona, and Chippewa Counties, collectively affecting well over a hundred cases, with dozens of convictions now being dismissed or vacated.

The BCA’s response has been to reclaim control of cylinder changes and promise new procedures. That’s a start, but it’s reactive.

If we apply the Five Whys, asking why each failure occurred, the real problem isn’t operator error. The system was built to allow those errors.

1. Why Are We Still Relying on Manual Typing for Critical Data?

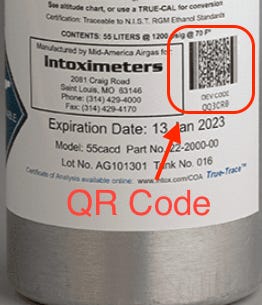

Every dry gas cylinder used in a DataMaster breath test already comes with a QR code or barcode that contains its lot number, concentration, and expiration date. Yet the DMT still requires operators to type that information manually.

A simple barcode scanner mounted next to the instrument could populate these fields automatically. No typos, no transposed digits, no “oops, wrong number.” This kind of automation is standard in every other industry that relies on traceability, from clinical laboratories to blood banks.

If a grocery store can scan a bag of chips and instantly pull up its batch data, a forensic instrument deciding someone’s guilt should be able to do the same.

2. Why Are Minimally Trained Officers Changing Scientific Controls?

Changing a dry gas cylinder isn’t like replacing a printer cartridge; it’s a quality assurance procedure that directly affects the reliability of every subsequent test.

In Minnesota, law enforcement officers with minimal scientific training have been responsible for installing new cylinders and entering the data manually.

That’s not how scientific quality assurance works. In a forensic laboratory, a task that affects calibration is performed by trained analysts and peer-reviewed before use.

Why would we allow officers with less training than BCA scientists to perform this procedure without peer review?

Allowing officers to perform this step was a decision made for convenience, not for forensically sound practice.

The DMT’s software should restrict that function entirely to qualified BCA scientists or other highly trained technicians. The instrument already has the ability to enforce this through secure logins and access levels.

This safeguard is not radical. It’s a basic laboratory discipline that should have been there from the beginning.

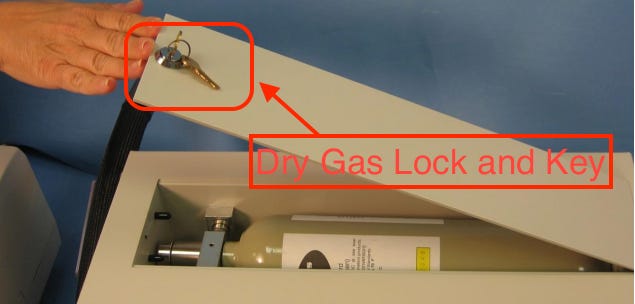

3. Why Isn’t the Gas Compartment Physically Locked?

Even with software restrictions, the simplest and most reliable safeguard is physical: a lockbox over the DMT’s dry gas compartment.

The instrument’s manufacturer actually sells this lockable back housing. It’s a simple modification: a sturdy, keyed metal enclosure that prevents unauthorized access to the cylinder.

If this had been standard from day one, many of these errors simply could not have occurred.

The lockbox turns what was once an open compartment into a controlled-access area, just like every other part of a forensic instrument that affects analytical results.

4. Why Doesn’t the Instrument Detect When a Cylinder Is Changed?

The DataMaster DMT already monitors gas pressure in real time. When the pressure drops, it indicates that the cylinder is empty or has been removed.

With a simple software update, the DMT could require users to confirm a new cylinder installation whenever a drop in pressure occurs.

The instrument could prompt for a QR scan, validate the data, and force a control test before any subject tests are permitted.

That would turn what is currently a manual honor system into a self-checking system. The instrument could refuse to proceed with testing until the control material has been verified.

For something as consequential as breath alcohol testing, that kind of protection should be non-negotiable.

5. Why Isn’t There Verification When Instruments Return to the Lab?

Even if we fix everything in the field, there’s still a missing step in the chain of custody: what happens when a DMT comes back to the lab?

Each time an instrument is returned for calibration, maintenance, or storage, the dry gas cylinder and lot number should be verified against the record from when it was deployed.

If the cylinder doesn’t match or if it’s been replaced without documentation, that should trigger an investigation immediately.

This simple check would create a full-circle chain of custody for every control gas used in the state.

It’s low-cost, practical, and aligns with the quality assurance principles that forensic laboratories already follow for every other form of evidence.

The Real Root Cause: Minimizing the Problem Instead of Preventing It

The BCA’s decision to call this a “data entry” issue isn’t just inaccurate, it’s telling. It reflects a broader institutional pattern of minimizing errors rather than addressing their causes.

The truth is, this isn’t the first time the BCA has refused to fix a known problem. In 2007, the BCA received a software patch for the Intoxilyzer 5000EN that would have fixed a defect causing the instrument to reject valid breath samples.

But the BCA chose not to install the patch because it didn’t want to “draw attention to the issue.”

“The Minnesota BCA, responsible for maintaining the instrument, had received a software patch to fix the problem in 2007 but failed to install it, as they did not want to draw attention to the issue. Instead, the laboratory relied solely on the officer’s observations to identify the problem.” (Olson & Ramsay, 2025)

That decision meant people who provided valid samples were accused of refusing tests, and the underlying defect was hidden from the public for years.

The same instinct to manage perception instead of ensuring accuracy has now reappeared in the DataMaster DMT program.

From “Still Accurate” to “Shut It Down”

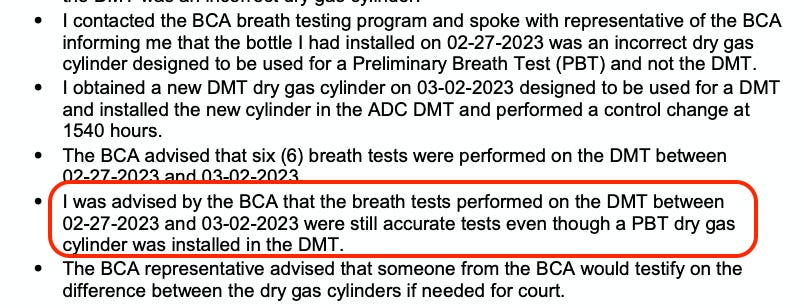

When this error first surfaced in early 2023, the BCA’s position was the opposite of what it is today.

In an Olmsted County Sheriff’s report from that time, a deputy recorded that the BCA had “advised that the breath tests performed on the DMT between 02-27-2023 and 03-02-2023 were still accurate tests even though a PBT dry gas cylinder was installed in the DMT.”

In other words, when the problem wasn’t yet public, the BCA insisted the tests were valid and even said they would testify to that in court.

It was only after our peer-reviewed publication in Forensic Science International: Synergy brought the issue to light statewide in June 2025 that the agency reversed its stance.

Recommendations to Prevent This From Happening Again

These failures are completely fixable, not with vague “procedure updates,” but with tangible safeguards.

First, automate data entry with QR scanning. It’s already built into the supply chain for dry gas cylinders, and the technology exists, so it would cost little to implement.

Second, lock down access to the dry gas controls. Only trained, authorized personnel should be able to install or replace cylinders. Every DMT in the state should have a manufacturer lockbox installed.

Third, when the cylinder pressure runs low, the DMT should automatically require a fresh control test before continuing operation.

Fourth, reintroduce laboratory-level verification. That means peer review, remote approval, and logging of every control change in a centralized database accessible for discovery.

Fifth, close the loop. When instruments return to the lab, verify that the same cylinder and lot number are still installed. If not, document it, explain it, and audit it.

And finally, the most important step is to restore transparency and external accountability.

If the BCA wants to rebuild trust in its breath testing program, it must begin making all quality assurance data publicly accessible or at least available in real time for independent experts to review.

A Final Word on Integrity

According to the BCA’s own stated core values, “Integrity is the cornerstone of public trust. This organization strives to always do the right thing.”

Those words matter.

Integrity isn’t proven by press releases or procedure updates; it’s demonstrated through transparency, accountability, and a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths.

If the BCA truly wants to live up to its own standard, it must open its data and welcome independent review.