When Science Meets the Gatekeeper: Minnesota Supreme Court Grapples With in Knapp v. Commissioner of Public Safety

Foundational Reliability, Observation Periods, and the Court’s Role as Gatekeeper

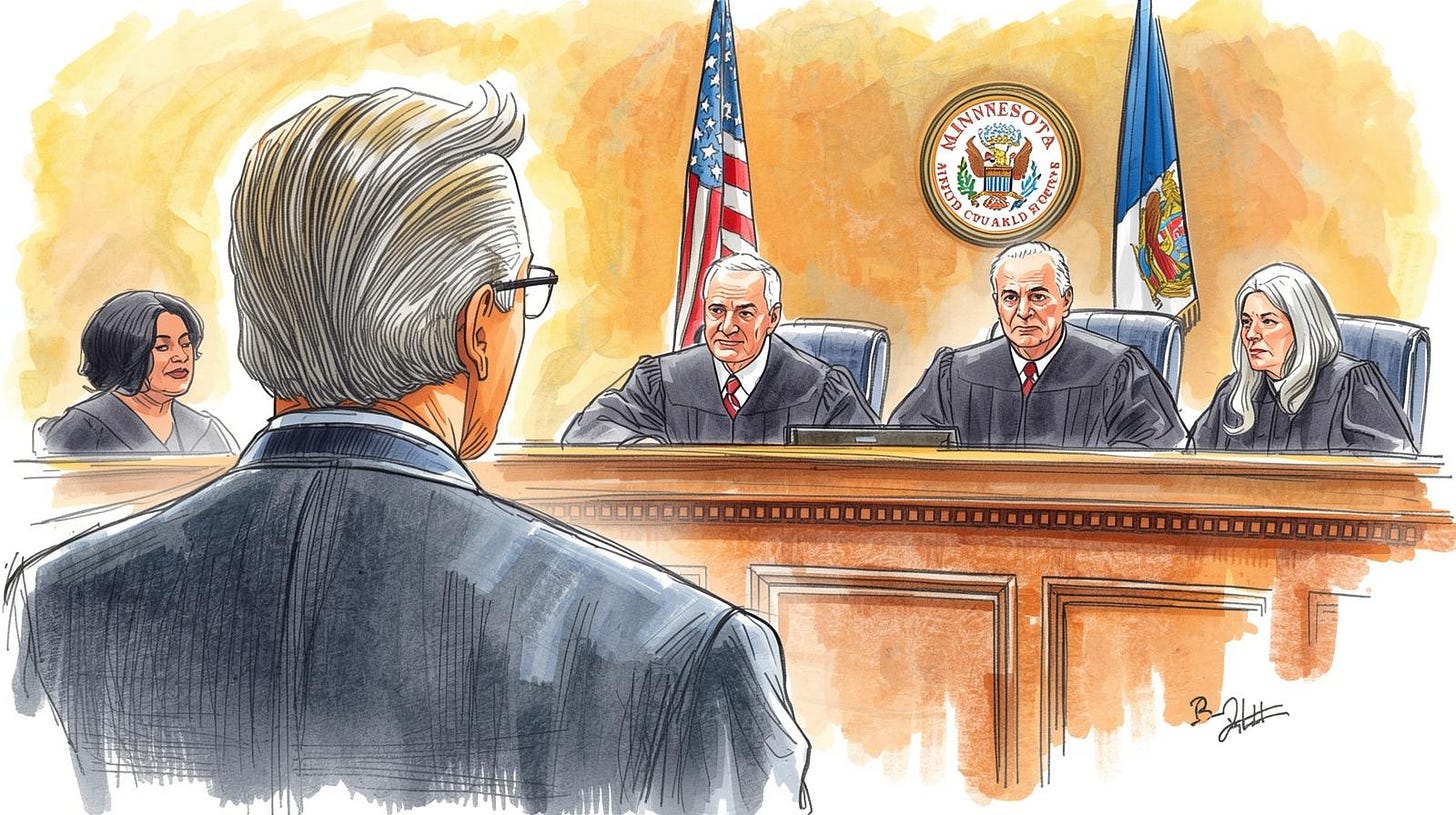

Yesterday, the Minnesota Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Knapp v. Commissioner of Public Safety. This case goes to the heart of how courts treat scientific evidence in breath alcohol testing.

At issue was not whether breath testing is generally reliable, but whether a foundational scientific safeguard, the pre-test observation period, must actually be followed for a test result to be admissible.

In other words:

Is it enough that an officer holds a certificate, or must the officer actually follow the procedures that make the test scientifically reliable?

The Observation Period as a Necessary Scientific Safeguard

Breath alcohol testing is designed to measure alcohol coming from the lungs. Alcohol originating from the mouth, whether from burping, regurgitation, reflux, or recent ingestion, is contamination of the breath sample.

The observation period exists to address that problem.

This requirement is clearly stated in the current and previous versions of the DataMaster DMT Operator Training Manual:

“A test subject should be observed for a minimum of 15 minutes prior to administering a breath test to ensure nothing is placed in the mouth and nothing erupts into the mouth.”

The Astrology Hypothetical and Why It Mattered

One of the most revealing moments in the hearing came when a justice posed a hypothetical that crystallized the Court’s unease with the State’s position:

“So the legislature could legislate complete bunk science. It could say an astrological test is per se admissible as long as the astrological test is certified by the commissioner of astrology.”

Astrology is inadmissible not because a statute fails to mention it, but because it lacks scientific reliability.

Should Breath Tests Have an Evidential Carve-Out?

Throughout the arguments, multiple justices questioned why breath tests should be treated differently from other forms of scientific evidence.

In DNA analysis, contaminated samples are excluded. In blood testing, improper collection invalidates results. In fingerprint analysis, flawed procedures undermine admissibility.

In none of these fields do courts say, “The analyst was trained, so the result comes in regardless.”

The State argued that breath tests should be admitted based solely on the operator’s certification and the instrument’s internal checks.

Several justices found that position difficult to reconcile with general evidentiary principles.

Training Versus Credentials

Another theme that emerged was the distinction between having training and following training.

A lab technician who ignores contamination safeguards does not produce valid results simply because they passed a certification exam years earlier.

The observation period is the primary human safeguard in an otherwise automated process. Treating it as optional strips the test of one of the test's basic scientific safeguards.

Remand and the Court’s Broader Concern

Multiple justices suggested that the case might ultimately be resolved through remand, allowing lower courts to apply a more traditional rules-of-evidence analysis rather than the rigid burden-shifting framework that has developed in implied consent cases.

The Question That Remains

At bottom, Knapp asks a simple question:

If a procedure is required to make a scientific test reliable, can courts admit the result when that procedure is not meaningfully followed?

Or does the failure to follow scientific procedures merely go to the weight and persuasiveness of that piece of evidence?