Ignored Warnings, Compromised Results: What Happens When Breath Test Operators Don't Follow Protocol

How software controls could eliminate common sources of testing error in breath alcohol testing.

My latest paper, Compliance by code: The need for automated protocols in breath alcohol testing – case reports, just published in Forensic Science International: Synergy, documents something I’ve been observing: breath test operators routinely ignore instrument warnings and violate established protocols.

Not because they’re malicious, but because the current system gives officers too much discretion in how testing is conducted.

The Cases That Shouldn’t Have Happened

Let me tell you about two cases from 2024 that illustrate the problem.

Case 1: The Interference Flag

A subject was being tested on a DataMaster DMT. The instrument produced an “Interference” message—not once, but twice. This message means the breath sample contained compounds other than ethyl alcohol.

The Minnesota DMT Operator Training Manual is explicit about what to do next:

“Obtain a warrant and collect blood or urine for analysis.”

Instead, the operator moved to a different instrument and obtained a numerical alcohol result.

The absence of an interference message on the second instrument doesn’t prove that the interfering substance disappeared.

It only means the interfering compound fell below that particular instrument’s detection threshold.

The same contaminant could still be present, still contributing to an artificially elevated result.

Case 2: The Observation Period That Wasn’t

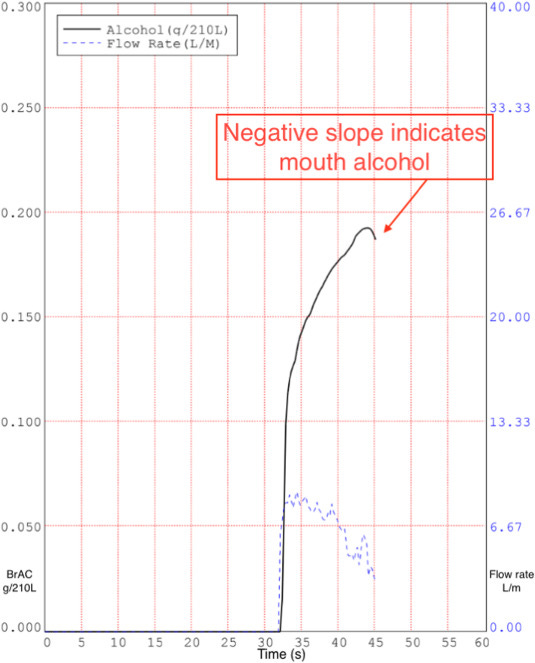

The second case involved a subject whose breath-testing sequence produced four “Invalid” status messages indicating mouth alcohol contamination.

Each one came with an expirogram showing a negative slope, which is a signature of mouth alcohol contamination.

During testing, the subject literally said, “Sorry for burping.”

The officer acknowledged this might indicate mouth alcohol contamination, telling the subject,

“I think the first one possibly could have been detected with mouth alcohol, so you might not even be that high.”

Then, continued testing without restarting the observation period.

To make matters worse, the subject was allowed to use the restroom unobserved during what should have been a continuous observation period.

On the fifth attempt, a numerical result was finally obtained. But because protocols were not followed, the validity of the final test was questionable.

Why This Matters

When protocols meant to prevent mouth alcohol contamination or interfering substances from adding to a breath alcohol test are violated, the measurement is no longer valid.

That’s why protocols exist. The protocols are designed to uphold quality assurance.

The Retraining Fallacy

The typical response to cases like these is predictable: identify the operator, provide additional training, document the corrective action, move on.

But this approach misses the point.

Retraining doesn’t address the fundamental problem: human decision-making in high-stakes moments where the correct choice might be inconvenient.

The Automation Solution

Modern laboratories have largely solved the problem through automation.

In toxicology labs analyzing blood samples, instruments follow programmed sequences that don’t change based on the technician's preferences.

Quality control checks are mandatory, not optional.

Why should breath testing be different?

Automated protocols in breath testing would:

Prevent instrument switching after interference flags through networked communication between instruments

Enforce observation periods by locking out testing until the required time has elapsed

Automation simply removes discretion from the areas where discretion creates vulnerability.

The Objection I Hear

“But this will make testing take longer.”

Yes. Sometimes it will.

And that’s exactly the point. When an instrument produces an interference warning, the scientifically correct response takes more time than ignoring it.

When mouth alcohol is detected, restarting the observation period takes more time than continuing with another test.

We need to decide whether we prioritize speed or scientific validity. We can’t have both in every case.

Judicial Precedent

The North Dakota Supreme Court recently decided Gackle v. North Dakota Department of Transportation (2025), ruling that failure to observe the full required observation period before retesting constituted a deviation from approved methods and rendered the results inadmissible.

This case signals that courts are starting to take protocol compliance seriously. But we shouldn’t need judicial intervention to enforce basic quality assurance practices.

The technology to automate these safeguards exists right now.

The question is whether breath testing programs value consistency and reliability enough to implement it.

The Bigger Picture

The lesson from other forensic disciplines is clear: standardization and automation improve reliability.

My article documents just two cases, but they represent a systematic problem.

Until we acknowledge that breath-test operator discretion is a bug, not a feature, we’ll continue to see protocol violations treated as isolated incidents rather than symptoms of a flawed system design.

The evidence is clear. The solution is available. The only question is whether breath testing programs will act on it.

You can read the full article in Forensic Science International: Synergy.