Beyond the Two-Hour Rule: What Toxicologists Get Wrong About Alcohol Absorption

Individual variation matters when it comes to alcohol absorption

I’m happy to announce the publication of my latest article, “Extended absorption, implications: Rethinking alcohol pharmacokinetics in forensic calculations,” in the Medico-Legal Journal today.

This paper addresses a critical gap between what the science tells us about alcohol absorption and what actually happens in forensic casework.

The Two-Hour Rule That Isn’t Really a Rule

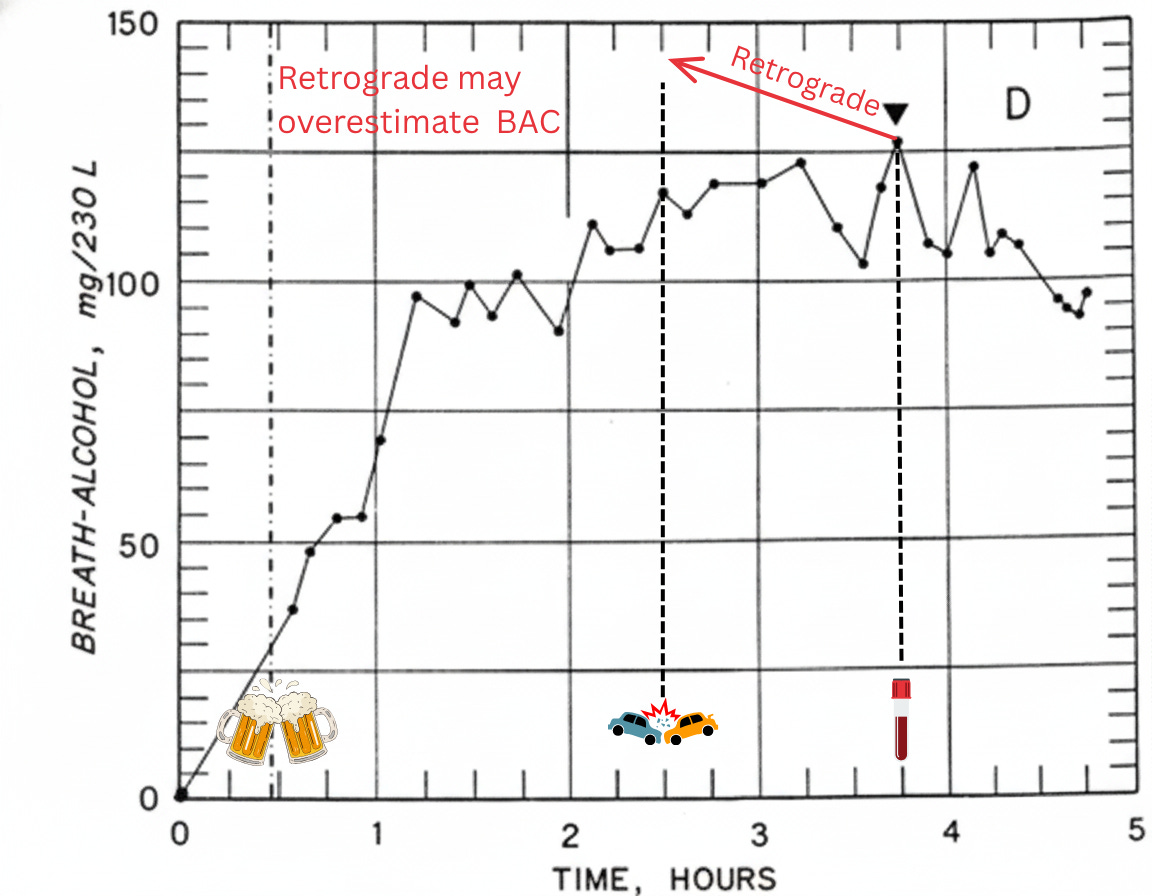

Here’s a scenario that plays out in courtrooms across the country: A driver has dinner with drinks, crashes two hours later, and gets blood drawn an hour after that.

A forensic toxicologist performs a retrograde extrapolation, working backward to estimate what the driver’s blood alcohol concentration was at the time of the crash.

The standard assumption? Alcohol absorption was complete within two hours of the last drink.

But what if that assumption is wrong?

Through a data practice request, I obtained and analyzed 36 retrograde extrapolation reports from the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension’s toxicology section from 2023 to 2024.

The findings were striking in their uniformity: All 36 reports assumed absorption was complete within two hours.

None adjusted for food consumption, medications, medical conditions, or trauma. Only one even mentioned that blood loss from trauma could delay absorption.

What the Science Actually Shows

The scientific literature paints a very different picture from this one-size-fits-all approach:

Individual Variation is Massive

Dubowski’s seminal 1985 review documented a 14-fold variation in time to peak blood alcohol concentration among healthy individuals, ranging from 12 minutes to 3 hours. One subject in his data took approximately 3.25 hours to reach peak concentration.

Food Changes Everything

Jones and Neri’s 1991 study showed that consuming alcohol with a large meal dramatically alters absorption patterns. One subject didn’t reach peak concentration until 230 minutes, nearly 4 hours, after finishing drinking. The researchers specifically cautioned against retrograde extrapolation without considering these individual variations.

Medical Conditions Matter

People with GERD showed average peak BAC times of 3.5 hours (range: 2-5 hours) compared to 2.5 hours in healthy controls, according to Booker and Renfroe’s 2015 study. The pathophysiology of GERD delays gastric emptying, keeping alcohol in the stomach longer before it reaches the small intestine, where most absorption occurs.

The GLP-1 Factor

Here’s something forensic toxicologists need to start thinking about now: millions of Americans are taking GLP-1 receptor agonists like Ozempic and Wegovy.

These medications work partly by deliberately slowing gastric emptying. It’s gastroparesis by design.

If they’re doing what they’re supposed to do therapeutically, they’re almost certainly affecting alcohol absorption kinetics. An emerging study has already found that these medications delay the rise in breath alcohol concentrations compared to controls.

Why This Matters in Court

When an analyst performs retrograde extrapolation while someone is still in the absorptive phase, the calculation will overestimate their blood alcohol concentration, potentially by a significant margin.

This isn’t a minor technical quibble. It’s the difference between a BAC estimate that reflects reality and one that doesn’t.

Current professional guidance acknowledges that “studies support that it can take up to 2 hours” to reach post-absorptive status, but doesn’t provide methodology for evaluating cases where absorption extends beyond that timeframe.

The ANSI/ASB standard for alcohol calculations doesn’t require systematic assessment of case-specific variables that could substantially prolong absorption.

What Needs to Change

Forensic toxicologists should:

Evaluate each case individually for factors that may extend absorption beyond two hours. They must look at detailed consumption history, food intake, medications, medical conditions, smoking, and trauma.

Consider longer absorption windows when uncertainty exists, rather than defaulting to the two-hour assumption.

Document and justify the factors considered in determining post-absorptive status.

Explicitly state limitations rather than presenting calculations as having more precision than the science supports.

The Bottom Line

The human body doesn’t operate according to arbitrary time limits.

Evidence shows alcohol absorption can extend 2-5 hours beyond the last drink, depending on circumstances.

Dubowski himself expressed skepticism about retrograde extrapolation precisely because of this variability, stating that “no forensically valid forward or backward extrapolation of blood or breath alcohol concentrations is ordinarily possible in a given subject and occasion solely on the basis of time and individual analysis results.”

Individual physiological variation isn’t an exception we need to account for occasionally—it’s the norm. Our forensic practice needs to reflect that reality.

The article is now available in the Medico-Legal Journal: https://doi.org/10.1177/00258172251382701